K-SCORE: 55

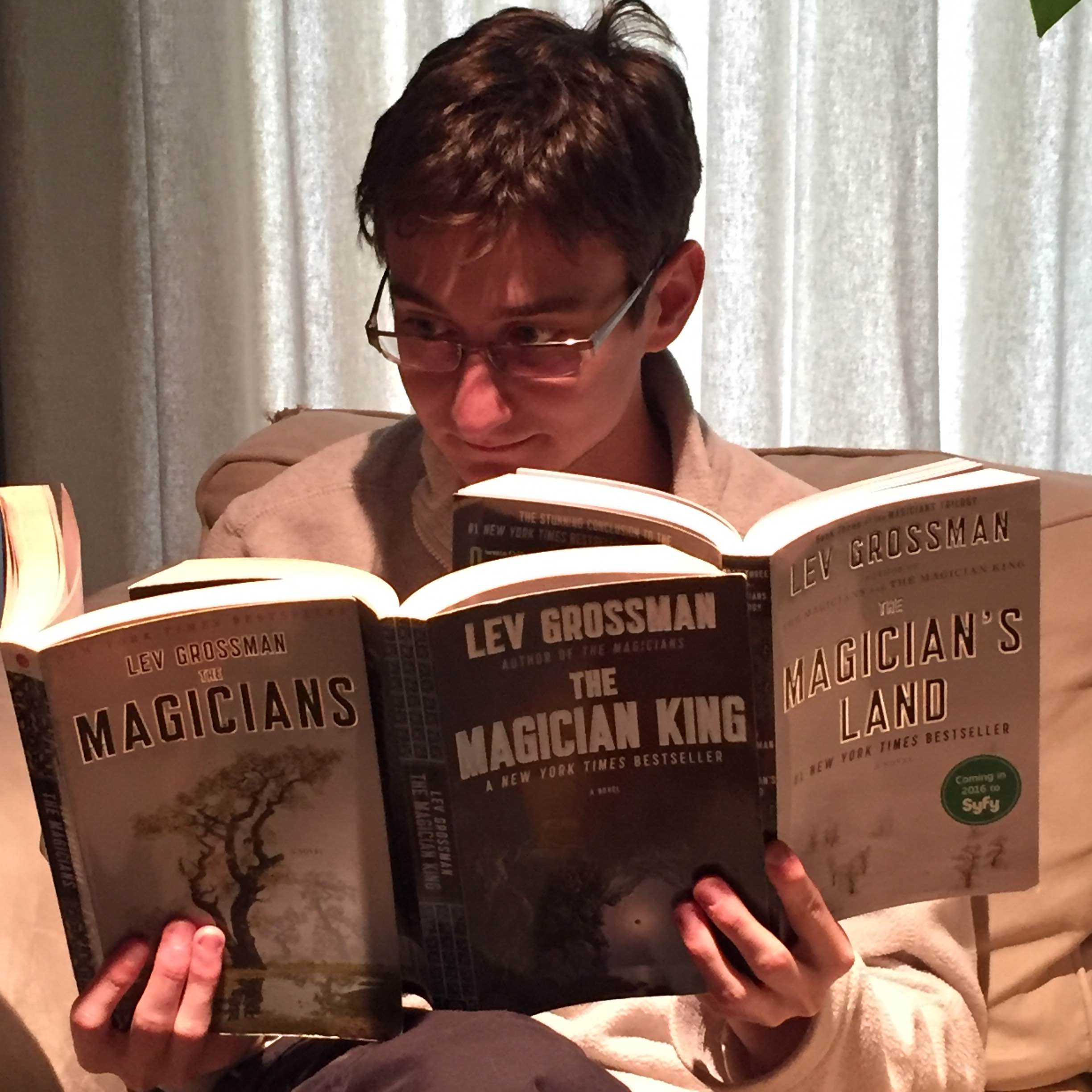

Author: Lev Grossman

Spoiler Level: Major

“Grossman, in the end, showed an excellent degree of understanding for his characters and his world, and did his best to take them to good places after he’d spent so long pissing all over them and kicking them into a very deep ditch.”

“you’ll almost wish it was all just published in a single fat volume”

This series took me on quite the ride. It has very deep issues, but my growing understanding for it and appreciation for what it does do well or poorly, even right or wrong, is thoroughly complex. To show you what I mean, here’s what I wrote about the first two novels:

After having read The Magicians and The Magician King, I was forced to consider something I try to steer away from when analyzing a piece of fiction. For however harsh my words, and for however hard I can be on stories with which I found fault, I never want those criticisms to be attributed to the creator. I don’t know these authors. I don’t know the directors, actors, screenwriters, and game designers either. And, as someone who respects depth, I don’t think the shallow Tweet-media we have does a good job of getting at the real personalities and commendable or condemnable qualities of people in the public eye. Which, in a way, speaks to the power of what Lev Grossman created in the first two novels in his series because after having read them, I now strongly suspect that he is not a good person.

It might seem cruel of me to make a judgment about the author’s character from just two novels, and I fully accept that I could be wrong about the man I’ve never met, but the content, themes, and style of these books screams to me that it was written by an asshole, a man who wants to be cool above all else and assumes he’s ethical despite his actions and views.

I write that because that is the essence of the plot and narrative tone of much of The Magicians and The Magician King. Quentin, the protagonist, is on a quest. For much of the time he is an entitled student or king, comfortable and safe, who doesn’t understand the meaning behind what he’s doing or even its base purpose, yet he plows head first anyway in the land of no wisdom at the mortal peril of ancillary characters.

“Quentin wasn’t the only character I found deplorable”

The problem is worst in the second half of The Magicians. That novel starts out great. Quentin is a smart, ambitious kid suited to discovering the secret magical world because of his intellect, dedication to studying the arcane, and natural affinity for sleight of hand / fake illusions on Earth. He meets a girl, Alice, even more interesting than he is, falls in love with her, then uses magic as an excuse to pursue nothing in life and spiral into the depths of alcohol abuse, drug addiction, and infidelity. His actions are deplorable enough that I was at the point where I hoped the story would end with him sacrificing himself for that which he really loves: Alice, the girl with both the talent and the moral grounding to thrive as an exemplary magic wielder in their world. Quentin has only the former. Alas no, the exact opposite occurs. After discovering Narnia, oops I mean Fillory, really exists, Alice sacrifices herself to save Quentin and a few paltry characters even more mean-spirited, selfish, and irresponsible than him.

Alright so that’s frustrating plotting, but it could work as the seeds of a story about the harsh realities of a universe, even a magical one, and it could have been the start of a meaningful journey of understanding and change for Quentin and for the other magicians. The first novel ends terribly because Grossman doesn’t seem to understand what really happened in his story. There’s no value gained from the end (in spite of the kingship and queenship of the surviving characters), an incomplete or unacceptable understanding of the despicable nature of Alice’s demise, little hope for wisdom, and no steps taken towards positive change by anyone. He treats Alice’s death as an unexpected plot twist, a - you didn’t see that coming sucka! - moment, and his cruelty to his best character (she dies in the precise manner of her dead brother that plagued her past) rubs off on the reader in a profoundly unpleasant way. It’s more than just evil for evil’s sake, and it’s more than the kind of tragedy that makes you search hopelessly for answers in life, meanings behind what has happened. It’s moral blindness, rewarding moral blindness, and attempts to garner sympathy for the morally blind. At the very end of The Magicians, Quentin is sucked back to fairytale adventure land only with boobs and fine wine to live a life as royalty in Fillory.

Enter The Magican King. Right from the get go, I was frustrated by Quentin treating Alice’s death as the sad inevitable disaster that befell him. Him! As if Quenitn is the victim. Alice, who is wiser, better at magic, faithful in their relationship, kind, who sacrifices herself for him after he betrays her and dragged her to a dangerous place for no good reason, is not given any degree of respect or remembrance from our protagonist. And yet again, there is a Grossman assumption that Quentin, just from his very nature of being the protagonist, is a good guy regardless of whether or not he does good things. This is apparent on close to every page, making for a gut-churning read. I couldn’t help but feel like Grossman, through writing, was showcasing his own blindness and using his story as an excuse to validate whatever dickishness, douchbaggery, and moral crimes he’s guilty of in his real life.

The Magician King is worse than its predecessor for a few reasons, but chiefly among them is that Alice is replaced with Julia, who is almost Quentin-esque in her opinions of life and people and simultaneously not that interesting.

Fillory is twice as prominent here as Quentin is a king in Fillory for much of the novel and his quest for seven golden keys (I shit you not) takes place there. The place is Narnia. The biggest change is that Aslan is a ram god instead of a lion god. First off, it’s weird that Grossman feels comfortable packing his prose with every cultural reference and fiction reference imaginable except Narnia, which he made real and changed the name of. He mentions Harry Potter, Gandalf, Die Hard, the land of the Teletubbies, and so on, as fictional places of Earth lore in his universe. From there to just go to Narnia and have a Narnia adventure is creatively bankrupt. Adding sex and blood to C.S. Lewis’s magical place doesn’t make it yours.

And then the quest itself - holy hell. Quentin embarks on a ship that’s special because he says so, on an adventure that Grossman overtly says many times, “will just reveal its purpose in time,” and will inevitably lead to a conclusion whereby the characters are richer for the journey. Why not? That’s what happened in Narnia and they’re in Narnia and know it’s Narnia because they’re older, and read the Narnia books when they were kids. Quentin constantly talks about how no step can be a misstep because they all lead to the end where they collect seven golden keys, find out what they’re used for and unlock a panacea. Believing all roads lead to the same inevitable ends and that you’re a good person regardless of what you do is a very dangerous way to live life. Quentin, if it’s true that all random choices lead to the same ends, why didn’t you just sit in an alley and masturbate at the sight of passersby because eventually that’s going to save the fucking universe? And honestly, that’s how it felt a lot of the time.. A choice with no consequences is hardly a choice at all.

When Quentin did get to the point where Penny, the character with knowledge and solutions to things (who obviously sucks according to Quentin) tells Quentin what the whole point is, he returns to Fillory (getting back had been all he’d been trying to do for a hundred pages) and discovers his friend Eliot has already completed five-sevenths of the job using the “Whatever. How about over there?” tactic. At the end, Quentin unlocks the magic door, saves everything from “the gods” (uh… alright) and is forced to hit the reset switch on his given circumstances. But he’s a better character now. Developed. Why? Because Lev Grossman says so. This appears on the last page: “But something had changed inside him too. He didn’t understand it yet, but he felt it.” … change, but no understanding… sensing a pattern?

The better part of the novel is the slow interspersed chapters telling the backstory of Quentin’s estranged childhood friend Julia who doesn’t get into magic school in the first novel and has to learn magic the hard way. I actually liked that premise. Yet arrogant Julia is a clinically depressed girl who lusts for power and doesn’t know why. She is unpleasant for others to be around, sleeps with people to advance her underground magic career, abandons her family even when they cared for her and gave her many chances to behave better by them and for herself, and throughout all that she constantly feels sorry for herself, for her circumstances, without ever letting another person get emotionally close enough to express sympathy or help her out. She gets tangled up with the ultra elite untamed unlicensed magicians, and to be fair, has a nice moment where she decides that the backwoods intellectual snobs, all of whom are computer hackers, make her feel a part of something like family and friendship. That’s quality story development and meaning garnered from a trying character experience. You only get a small dose of that antidote in the poisoned product, however.

Despite the tone of my review here, I was simply disinterested, bordering on apathetic, as the magic became less consistent, as I met yet another “master magician, so powerful you can’t understand,” kind of character, and another world-rending plot or plot device. That was until about page three-fifty of four-hundred.

The crux of the novel, the core of anything interesting it has to offer as a work of art, is in the content of the penultimate chapter. Julia and her Murs magician friends have been looking for a means to far greater magical power and discover they’re onto something by researching religions of very old cultures. After gathering info, they perform a summoning ritual for a benevolent forest goddess. Not-so-surprisingly, the ritual goes horribly wrong and they end up summoning a trickster god who isn’t so nice after all. I freely admit that I was very surprised when that twelve-foot fox-headed giant, who’d just brutally slaughtered almost all of Julia’s cohorts, picks Julia up, puts her on a stone pedestal, tears off her white robe, rapes her for “seven to ten minutes,” and sucks out her soul with his penis, leaving her a bloodied “unfeeling” shell of a human being. At first I thought, wow, that was powerful, and it was, but that doesn’t make it a good story. It’s close, but not quite there. Firstly, the rules of magic, the gods, and the multiverse in these books are so sloppy that a lot of the potency of the moment is lost just because the god’s character, plan, and own circumstances either didn’t make sense or weren’t delivered at all. That would have been incredibly affecting if that god became an antagonist, but he doesn’t. He rapes Julia and departs the story. Worse than that though, is how Grossman treats the rape. I’m sure feminists could have a field day with it. I don’t think there are rules that say a man can’t write a story of a woman getting raped, but Grossman is particularly ill-equipped to handle such content. Want evidence? About ten pages prior he wrote in a Julia chapter, “There was enough hiding in life. Sometimes you just wanted to show somebody your tits.” Hm… I’m not sure he’s mastered female sexuality.

My biggest gripe with the rape, though, and therefore the whole book, is how Grossman wrote that Julia loses her soul when it happened and couldn’t feel anything anymore. Firstly, a character who can’t feel anything, who is emotionally defeated, isn’t that interesting. Am I to believe during the whole present time segment of the novel Julia is just an unfeeling husk of a human? And secondly, what wretched commentary is that on rape victims? They lose their souls. They’ll never love again. A fate worse than death. A man took her reason for being with his brutality. Those things are both untrue and unethical to believe.

Maybe Lev Grossman realizes that and Julia’s story will continue in another book where she learns a potent way to fight Reynard the Fox, but I doubt it. I think he thinks he did some resolving by calling her a dryad, turning her even more beautiful, and having Quentin open a magical door for her.

So, two-thirds of the way through the series, Grossman has done untold damage to his story, characters, and possibly himself.

“often tells instead of shows”

Enter The Magician’s Land:

The conclusion to Lev Grossman’s Magicians series left me stunned. The Magician’s Land is a supremely impressive work of fiction. It’s not one of my favorite novels. It doesn’t excel at any one aspect to a remarkable degree. It’s not really even that good. Yet it makes truly incredible strides towards healing the grievous wounds inflicted on the series by the first two books, salvaging some of what made the first couple hundred pages of The Magician’s good, and building new traits onto the existing constructs that make for a more rounded, satisfying, less ethically horrifying, and more entertaining story. Grossman, in the end, showed an excellent degree of understanding for his characters and his world, and did his best to take them to good places after he’d spent so long pissing all over them and kicking them into a very deep ditch.

The new character of substance in The Magician’s Land is Quentin’s new young Brakebills-expelled apprentice Plum, who has Chatwin ancestry. I didn’t see the point of her for a long while, but her story does serve two vital functions. For one, she exemplifies the difference in the series of a twenty-two-year-old magician and a thirty-year-old one. It’s not that Plum is hedonistically horrible, as Quentin and company were in the others, but rather that she has a naivete and an accompanying optimism that show that magicians travel unique and whimsical paths, linked inherently to their developing power and maturity. You can see how far Quentin has come through her and her friends. More important than that though, Plum and Quentin don’t sleep together! This isn’t character development for Quentin just because Grossman told me so, but rather evidence than he is a more temperate man, willing to have complex relationships with a variety of people without selfishly seeking to satisfy every urge he has first and foremost. Throughout the novel there are a lot of tempting circumstances for both Plum and Quentin, from being naked in the arctic after their blue whale journey, to living alone together in Plum’s NYC rowhouse, and both characters handle all those temptations very well, without losing their sense of fun, without developing a belief in their superiority or infallibility, and without neutering the entertainment inherent to those circumstances.

Plum exemplifies just a touch of Quentin’s development, however. Several times throughout the story he puts himself in a position where he may potentially be sacrificing himself for something he cares about even more. Those things: Fillory and Alice! Yes, that’s what Quentin cares about, Grossman. You do understand it. Quentin works through his journey to discover the nature of Alice as a niffin and puts himself in grave danger to face her, eventually taking Plum’s potent advice to deal with her directly, and brings her back from the demonic pure-magic entity into the realm of the living. The chapter following this success, Alice is brutally mean to Quentin, expressing profound hatred for all that he’d said and done in their past, but Quentin doesn’t argue. He takes it like a man. Yet Alice is wrong about much of it. And there’s something horrifying about her addiction to the power and her addiction to the sense of “not caring” that goes along with being a niffin, and Grossman lets the reader realize that slowly. Then equally slowly, he has Quentin reintroduce Alice to bits of life as a living, feeling person, that demonstrate why the accompanying weaknesses of a corporeal form and emotions beyond apathy are far superior to the omnipotent force of destruction she was. Alice comes back. Quentin even says, “I didn’t do it for me,” and later, “Quentin loved having Alice alive again. It was absolutely the greatest thing ever. Whether or not she loved him, whether or not she could stand the sight of him, the world, any world, was just so much better with her in it.” (371) This is an impressive shift for Quentin considering his actions earlier in his life, and as Alice decides to stay with him at least for a while longer, he says that in their past, seven years prior, Alice was, “in love with the person she thought he could be.” Again it’s a beautiful and profound change.

The evolution of Quentin’s attachment to Fillory is also profound. The title illuminates both his primary magical journey and the theme of him coming to understand, save, and move on from his love of the world within the books he read as a kid. Quentin must fight to save the place that first made him feel magical when he was just eight-years-old, eventually rebuilding and reshaping, becoming a part of it and leaving it behind all at once. Through Quentin, you can feel Grossman’s love of these magical worlds, Narnia of course specifically, and there is a very powerful message about the joy of absorbing someone else’s magical creation, someone else’s world and story, and then moving on to make something unique to your personality. Obviously I found it supremely relatable. By cutting away Ember and Umber, the all-knowing, all-powerful Gods, he gave Fillory a chance to be more than a carefully controlled place where everything always works out for the best - he gave it the freedom to decide its own fate in the hands of those that live there, and those that fall into its magical realms.

In the previous entries, Quentin wasn’t the only character I found deplorable. Eliot and Janet and Julia all have their ugly patches, and to varying degrees of success, Grossman works on them as well. Janet especially becomes more than just a selfish bitch, even if she doesn’t grow a tenth as much as Quentin. There’s a story about Asmodeus / Betsy hunting Reynard on Julia’s behalf that helps sweeten the sour taste of The Magician King rape, but honestly having that go on in the background isn’t close to enough given the horror of that content. These old gods, these antagonists seeking to eradicate magic and torment humankind needed more than a hidden dagger and a background character. They needed a complex structure ruthlessly obliterated by a team of like-minded and dedicated magic wielders. It’s something though, better than treating it all like it didn’t happen. Sadly, where Julia ends up, as a some tall dryad goddess, is largely meaningless. She’s too powerful and too uninvolved for me to have cared about her and her presence made me wonder why so much time was spent on her character at all.

Throughout this four-hundred page healing process, Grossman manages to maintain his highly readable and entertaining prose style, and inserts a great deal of powerful and unique magical elements to keep the story moving. The page from The Neitherlands is cool and comes back in an interesting way. The destruction of Fillory is potent, horrifying, and well described. The Chatwin story finally becomes clear and in a way that is meaningful and a cool blend of fairytale and dark reality. The Chatwin case heist is exciting, though I don’t know why Grossman chose to add and then completely drop Stoppard. And the alternate dimension where subtle things are different in Plum’s NYC house was stupendous. It’s so eerie in there! Quentin and Plum exploring the place they made without knowing the nature of what they’d done was simultaneously the essence of the magic in the Magicians trilogy and a rare feat of thrilling fantasy storytelling. Reading that made me feel like Grossman had again captured the intrigue of first discovering Brakebills and magic in general in The Magicians.

Yet I stand by what I said in my opening paragraph about The Magician’s Land that it’s perhaps not even very good. The reason is that simply too much damage had been done. Grossman has to spend the entirety of the novel fixing problems from the previous, which sometimes amount to just character development (so not problems at all), and other times amount to simply writing the opposite of whatever was written before. Regardless of which it is, it’s too much of it. There are so many sentences in The Magician’s Land where Quentin talks about being a different person or a better person, where other characters do the same, and even where the nature of the worlds and magic are mentioned to have grown and developed. Quentin needed to be somewhat of the same person, have some of the same personality. Where was his sleight of hand stuff? Where was his personal tastes for food and wine and whatnot? Where was his love for all things Fillory in the first three-hundred and fifty pages? And the novel often tells instead of shows and that’s because it has to. It would need to be three times as long to work through every single issue meaningfully. And even if the unsubtle way the novel has of telling the reader what has changed, improved, and developed wasn’t constant and bothersome, since there’s so much of that right from the start, there’s less essential time to work through the details of the magical plot. All the conflicts are rushed through with a snap of magic fingers. Boom, Quentin is kicked out of Brakebills. Boom, Quentin and Plum make a new land. Boom, Alice is returned to life even though Quentin never really discovered what a niffin is. Boom, Quentin’s a dragon fighting Ember. Boom, Fillory is fixed by his god powers. One after another after another. Yeah he hit the important points and he went in a better direction than I could have imagined, but it’s a story so wildly complex, dealing with multiple realities, an assortment of masterful magic wielders, mysteries large and small, hundreds of years of history, essential personal conflicts, and full-on apocalypses that it’s actually taken way too fast. Too many characters and too many moments didn’t have the impact they should have had if more attention had been paid to them. Quentin sure. Mayakovsky: close. Plum: no. Alice: definitely not. Janet: maybe. Julia: God no. Eliot: I’m never sure Grossman knew what he wanted to do with Eliot in the first place. Ember, Umber, Martin Chatwin, Jane Chatwin, Rupert Chatwin, Asmodeus, Penny, Josh, Poppy, Reynard, and Dean Fogg: well, minor characters are okay, but sometimes you want to better understand why they’re in the story in the first place, which isn’t always the case. In terms of place, The Neitherlands and Brakebills don’t come to vital story keystone points in the same manner as Fillory and Quentin’s newly created lands.

Considering the task Grossman had in front of him, it’s a great feat of writing just to get me to respect The Magician’s Land, which I do. I think I was pretty clearly wrong about Grossman being a total asshole. He may be a partial asshole, or have been an asshole in his past and used his writing to gain personal understanding, but there’s more than enough wisdom in the finale to his series for me to believe that he has an understanding of selflessness, friendship, love, imagination, and willpower. I still think he cheats with his magic system, doing whatever he wants with it whenever he wants, but for more opinions on that kind of fantasy writing, see my review for Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus or what I write about sympathy and naming in Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind. And much of Grossman’s magic is undeniably entertaining. Ultimately the series lands (hehe) in a decent place. If you’re going to read it for its unique blend of mature subject matter and whimsical childish fantasy be sure to commit to the whole thing. You’ll feel like shit along the way to the point where you’ll almost wish it was all just published in a single fat volume, but it’s worth it for those that are naturally drawn to this material. I wasn’t struggling to get through the prose or fighting to figure out what the hell was going on. That I thought this much about what the story means, how the characters behaved, and the connection between creator and creation is indicative that Lev Grossman did accomplish quite a bit, he just got way in over his head.