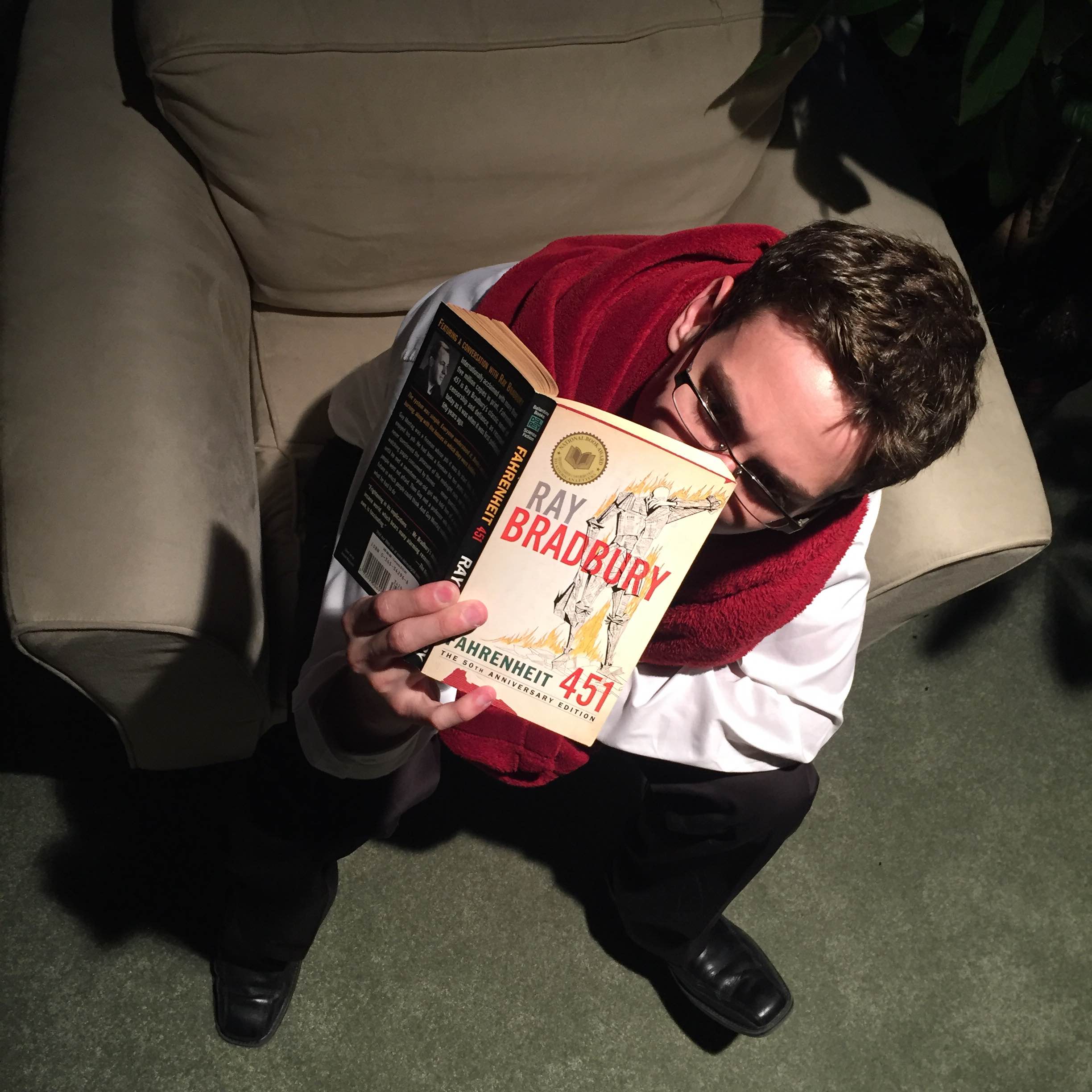

K-SCORE: 65

Author: Ray Bradbury

Spoiler Level: Moderate

Fahrenheit 451 is pretentious perhaps above all else. I disliked it about as much as a wannabe sci-fi writer and lover of liberty possibly could, which is to say that I found it interesting, I’m glad it was written, and I’m glad I read it. At first I found it to be exactly what I expected - a simple and easily supportable thesis on why you shouldn’t burn books just because the ideas and knowledge contained within can be frightening, offensive, or contradictory.

The more I read, the less I appreciated Ray Bradbury’s love of books and the more I became concerned with his desire to hammer political messages into place or tack up rants on his latest irritations with facets of his world. (Can you imagine what he’d be like nowadays in the world of media-shut-down Donald Trump and title-thieving Michael Moore?) Over time, Fahrenheit 451 loses focus. His characters vociferate about the state of their world, only their world is so flimsily described that it’s clear their complaints are about our world and exist outside the fiction. Many of Bradbury’s messages I agree with, but the structure gives me constant reason and ways to refute his points and become agitated with his sermons. By the end, I felt I was picking out things that Bradbury liked and didn’t like. People who drive very fast - bad. College professors - good. People who watch TV - bad. Poets - good.

I wanted to know more about the world of Fahrenheit 451, the hound that hunts Montag, how the government operates, what technologies exist, what families are like, what is taught to the children if they’re not allowed to read books. Instead I got monologues from Beatty about conflicting messages in books and how it’s easier if people are just happy, and monologues from Faber about how people used to listen to each other and read and think deeply about thing, and then lots and lots of Guy Montag being very very confused. His dawning realization that books might contain interesting things after all is not subtle, and his subsequent actions are neither interesting nor heroic. He’s just a lens.

Bradbury is very likely in the camp of “plotting leads to bad writing,” and “you don’t write your characters; your characters write you,” which I can understand why people would think that and want to work that way, and there is a grain of truth to it, but it’s basically a lie lazy authors tell themselves. His characters aren’t richer and his plot isn’t stronger from his process of sitting in front of a typewriter sixty years ago and hammering out pages. In fact, I had trouble envisioning his characters doing anything in his world outside of what he wrote. They exist only in the text he created and don’t have the strength to live in imaginations.

For all my complaints about this long-revered classic work of fiction, was it bad? No. The message that people constantly strive to suppress ideas that require thought and discussion, ideas that sometimes conflict or cause conflict, ideas that force people to face sad truths, to the point where they’ll burn them, is an important one. At the heart of Fahrenheit 451 is a novel that rages at those who seek either to ignore or silence any voice that is more than an echo of their own. Those people are everywhere, and at the time of its writing, were particularly powerful. It’s still totally relevant and some of the bits of the novel have proved prescient in guiding us toward those who would silence. So I’m thankful of this keystone piece of the genre and simultaneously thankful that most of the stories I read aren’t written like this now.