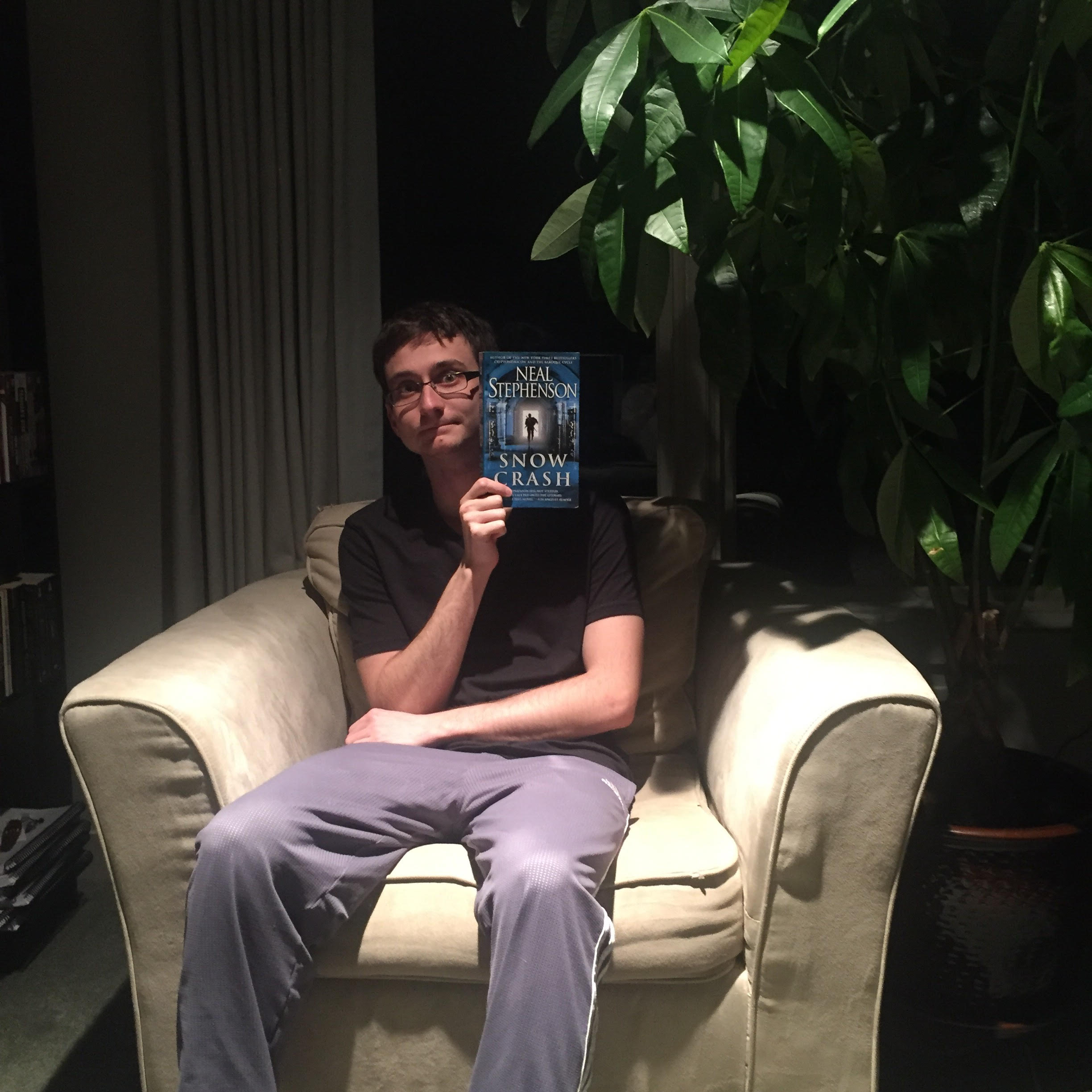

K-SCORE: 60

Author: Neal Stephenson

“Snow Crash ended up being a novel that made me wish the whole thing was about delivering pizzas in the future.”

Neal Stephenson’s science fiction debut Snow Crash squanders a tremendous amount of promise. He’s a particularly talented writer who chooses his subject matter well and whose voice is a rare combination of both edifying and entertaining. I discovered him through Cryptonomicon, which is actually a later work, and thought the same man exploring a genre more dear to me couldn’t possibly go wrong. Yet by looking at the two books side by side, I can see how Stephenson refined his skills and also where he continues to come up short. It’s not that Snow Crash isn’t a novel of some quality. It’s that it’s a tremendously disappointing read. Every page I begged to be a little bit better than the one before it, every chapter to give me something to latch onto and get excited about, and it never did. More and more the pages are filled with ramblings on Sumerian, gods, goddess, creation mythos, and neurological connections between mankind and software and less and less does the author seem to care about substantial plot and character development or solving any of his conflicts without guns and samurai swords. I like guns and samurai swords, but a smart book needs smart resolutions, and the absence of them is the strongest evidence that Snow Crash is little more than a fascinating premise propped up by a few of the pieces that comprise a narrative.

The novel opens with a couple chapters of superb prose outlining the protagonist’s job as a pizza delivery man in a semi-dystopian future world. It’s hilarious, entertaining, and compelling, as Stephenson simultaneously explains how important the task is, the mob connections, the success rate of getting them delivered in 30 minutes or less, and the stakes in the event of failure, while describing a rare scenario of potential failure. It’s a way to introduce Hiro, whose name rather unfortunately is the never-elaborated-upon Hiro Protagonist, and Y.T., a teenage kourier. But pizza delivery and the mob are largely irrelevant to where it all goes, and Hiro’s skills driving the car are meaningless next to the conflicts involving the virtual reality Metaverse and a digital virus that turns people into blubbering idiots. Y.T.’s aptitude for skateboarding through traffic is often relevant, but she’s an oddly chosen second to Hiro considering her age, ignorance, and general apathy.

“it’s as if when one of the two leads is doing something meaningful, the other has to be doing something irrelevant”

It’s okay when you think it might go somewhere exciting. When someone approaches Hiro’s avatar and tries to get him to try Snow Crash, the drug, and then he watches an old friend and hacker colleague fall victim to it, it makes you want to read on. But it’s as if when one of the two leads is doing something meaningful, the other has to be doing something irrelevant. Y.T. spends a few chapters making deliveries for the mob and being loosely tied to people loosely connected to people kind of investigating Snow Crash, which is all really unimportant considering how much time Hiro spends investigating it.

After someone he doesn’t know or care about gets gutted by a glass sword, Hiro, a sword fighter himself, takes to the Metaverse and picks up the research trail. Chapter after chapter, Hiro talks to an AI program with a lot of information and no personality. It’s worse than exposition. It’s Stephenson ensuring you have the major bullet points of all the research he did on the premise, linguistic, cultural, archaeological, and computer technical. I kind of got it right away. Snow Crash uses Sumerian, a mysteriously dead language, to trigger automated responses in people by reprogramming their brain stem. No matter how much you talk about the historical framework, it’s not getting any more plausible. I didn’t care about its plausibility. I cared about its theoretical application in the story, the dynamic of a virus in a world so reliant on the virtual, and the fear associated with having a virtual space no longer be safe for those in reality. That’s not at all what I got. In Ready Player One, Cline got stuck in a place where he couldn’t find a way to put real life danger into a story about a giant virtual world. I thought Stephenson had a one-up on that, yet it’s a lesser novel because the virtual reality is so lame, and they both feature some good old fashioned IRL permadeath.

Almost through luck, Hiro winds up on the same place as Y.T., Hiro’s ex-girlfriend and fellow Snow Crash researcher, the visionary that wants to use the drug to destroy / take over the world, and the angry Aleutian who can enact the plan and will because he wants revenge for Nagasaki. Guns, bombs, chases in the Metaverse, helicopter crashes, and last second saves from many of the characters that were briefly mentioned coincide for a conclusion that is lukewarm.

“the characters... don’t blur together but they don’t inspire emotional attachment”

Some writers have the problem that the characters are all emotional trainwrecks and all the conflicts end up feeling melodramatic, which can get annoying. Stephenson has the opposite problem. I think he must hate those kinds of stories so much that he’s afraid to write a character who has an emotional response to anything. Y.T.’s a fifteen-year-old girl who is wrapped up in this violent mission to stop a world-rending virus and is mostly irritated when people tell her she has to do something, kidnap her, or take her kourier gear. Hiro is a hacker, coder, and impoverished digital investigator and when people start dying in reality, he’s surprisingly calm about the whole thing. The other characters play things equally cool. Raven, Uncle Enzo, L. Bob Rife, the mafia men on the life raft, Juanita (who’s barely in it), the irrelevant band leader and roommate, Da5id, Lagos… they don’t blur together but they don’t inspire emotional attachment or conflict interest either. The characters were among the weakest elements of Cryptonomicon too, so this I was a bit prepared for.

What I wasn’t prepared for would be how little interest I had for the world Stephenson established. In Cryptonomicon, he got me to see my own world in a way that expanded my view of what it’s really like, its potential, and its true history. The Metaverse in Snow Crash is little more than a combination of Facebook and The Sims, and Stephenson doesn’t do anything with it other than insert one club, one office, and a really long street. The flotilla in the climax of the novel is a little interesting, but it didn’t feel meaningfully tied to anything. My favorite setting descriptions always occurred when the characters were in transit. The concept of a corporate conglomerate supplanting the government is something I’ve seen plenty of times before and never has it actually posed a radical sci-fi world I’ve found inherently fascinating. Stephenson’s is decent, what with people living in storage facilities and the Asians guarding their territory with mechanically enhanced dogs, but it didn’t spark anything that exciting in my imagination. Nor did it stretch it. That could be a feature of talking about future PC technology starting in 1992 though. Still, Heinlein did it better in the 70s.

Every once and awhile, Stephenson describes something in a way that makes you realize you’ve always kind of thought of it that way, or uses hyperbole to make you laugh at some absurdity that has a grain of truth to it. Periodically his conflicts are exciting, frightening, or tug at the heartstrings. Always his subject matter is carefully thought out and well researched, but that doesn’t make him the best storyteller. I’ll read others of his books, but I’m gonna stick to the later years in his bibliography for a bit. Snow Crash ended up being a novel that made me wish the whole thing was about delivering pizzas in the future.